Practitioner's Guide

Introduction

Welcome to the Practitioner’s Guide for AV Collection Holders! This is a practical tool meant to help archives and broadcasters with audiovisual collections to turn their cultural heritage assets into open educational resources.

For this guide, we’ve taken a simple approach in which you’re not bound by a rigid chapter-by-chapter structure. Feel free to explore its pages in the order that suits you best using the side menu.

Our aim is to provide you with a comprehensive yet accessible resource. One of the highlights of this guide is the diverse array of real-world examples. We’ve scoured the landscape of AV cultural heritage institutions to bring you initiatives that are already making impacts on education settings. These case studies span a wide spectrum, showcasing creative solutions, best practices, and lessons learned. As you read through these examples, you’ll gain insights that you can adapt and apply to your own unique context.

This guide was written from the perspective of the AV field to practitioners from the AV field. It means that we want the guide to be as practical as possible. We aimed to avoid long explanations and scholarly debates, though we’ve made an effort to recommend supplementary reading materials that could provide deeper insights into certain topics.

This guide is one of the outcomes of the project Watching Videos like a Historian, an initiative that brings together history and media professionals across Europe. The project partners believe that quality education is vital in countering the eroded trust in traditional media. In this sense, media literacy, particularly with audiovisual content, is essential in history and citizenship education to foster critical thinking and source evaluation.

For whom is this guide designed?

This Practitioner’s guide is dedicated to audiovisual collections holders. It means that, if you are a large or a small institution and you have some sort of audiovisual material, this guide is for you. As stated above, the idea is that you use this guide to help you out with opening up your AV collection for educational (re)use.

What is this guide?

We all know that opening up cultural heritage for educational purposes is a desirable necessity. However, sometimes it is difficult to transform the desired goal into clear action. Many questions can arise during the process of becoming more openly available, and this guide aims to answer them.

We want to present you with clear indications and examples of how to facilitate access to your AV collection. Because we believe that clear information works better if you can see in practice what we explain by words, we will provide examples of initiatives currently in operation.

The guide also intends to show that the use of AV material in educational settings can help students with an experiential approach and affective engagement, so that they don’t feel disconnected to the history they’re studying. The idea is to show, through moving images, that the historical fact is populated by real people, living their real life, offering the students the opportunity to go beyond the grand narratives in history.

This guide offers:

- Practical information about how to open up your AV collection for educational purposes

- Examples of initiatives already implemented in different places to be of inspiration for you to initiate your own activities

- Links to a more in-depth discussion about specific topics

This guide does not offer:

- Philosophical and scholarly discussions

- Individual consultation

Audiovisual collection consists of:

- Films and videos

- Sound recordings

- Microfilms

- Photographic images

- And digitised material

A brief overview of the methodology used to create this guide

We employed a multifaceted approach to gather insights for this guide. The first step was to compile ideas from the Watching Videos like a Historian project’s partners aimed at fostering diverse viewpoints. Based on the project partners’ recommendations, we curated examples and initiatives of recent projects on the use of AV collections in educational settings. We also conducted three semi-structured interviews with professionals from the audiovisual heritage field working with education and media literacy. The focus of these interviews was the challenges and opportunities that AV organisations hold when working with education and how they already give access to the institutional collection. Additionally, we have examined relevant research and other studies on digital collections, media literacy, copyright and the use of AV collection in educational settings, to help identify and organise the information we want to share with this guide. This methodology encompasses, therefore, real-world examples and initiatives, collaborative input and expert viewpoints, and a literature review to provide relevant and up-to-date information. Have a fun read!

DISCLAIMER

The insights (in the format of quotes) presented in this report are drawn from anonymous interviews conducted with professionals in the cultural heritage field. The names and affiliations of participants have been hidden to ensure confidentiality. To create this guide, we have translated all the original audio recordings and transcriptions from Dutch. Throughout the guide, you will come across quotes set apart with distinct font sizes, colours, and right alignment. These highlighted citations correspond to statements from our interviewees. In cases where different references are used, the appropriate source will be provided alongside the citation.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

As you navigate through this guide, it’s important to consider the perspective from which it was written. As mentioned above, the education experts who have contributed to this guide have their root in Dutch heritage institutions. Additionally, the examples and initiatives cited throughout the guide are predominantly from institutions in Western Europe. Despite our efforts to include a variety of viewpoints, we recognize that the guide may still predominantly reflect a Western perspective. This implies that the guide may not fully address the heterogeneity of material circumstances, needs and challenges faced by AV collection holders in other parts of the world.

AV collection for educational (re)use

Why should you share your AV collection as OERs?

All the discussion around making your collection broadly available sounds perhaps a bit too appealing, right? In a brief search on the internet you can find many reasons why open learning materials are important (the text is in Dutch but you can find more discussions HERE). You can easily find strong arguments to justify why educators should complement their lessons with open learning materials. But why should you share your AV collection? What are the advantages for your institution to share AV collections as OERs?

In this section we will present to you 5 reasons why this is important. We are well aware that each cultural heritage institution has its own motivation to open more or less its digital collection, but we want to provide you with some extra insights to motivate you to become more digitally open.

OERs (Open Education Resources) → according to UNESCO OER are learning, teaching and research materials that are in public domains or under copyright released as open licence. (Learn more: Creative Commons & UNESCO)

Why open up your AV collections for education purposes?

- Increase the number of educational materials available for educators and students

- Amplify the possibilities for teaching and learning onsite and remotely

- Allow educators to digitally create and organise lessons to use onsite and/or remotely

- Enlarge possibilities to share curated lessons facilitating the connection between the different materials

- Amplify cultural awareness and create space for marginalised students to have access to different cultural assets

By opening up your collection for educational purposes, you will…

Increase the number of educational materials available for educators and students

In recent times, formal education has been going through quite the transformation, embracing all sorts of materials to make learning more enjoyable. Imagine if your institution became widely recognized for sharing its collection and taking education to the next level. Sharing your collection as OERs can enrich educational content by providing real-world examples, primary sources, and visual materials. At the same time, it can enhance the valorisation of your collection through education. Audiovisual content, such as historical videos and documentaries, can bring subjects to life, making learning more engaging and impactful.

Amplify the possibilities for teaching and learning onsite and remotely

Another positive societal outcome of sharing your AV collection as Open Educational Resources (OERs) is that it significantly contributes to expanding the potential links between diverse cultural elements. This means that through digital access to resources, educators and students can establish connections among various artists, themes, subjects, historical periods, geographic similarities or differences, leading to more profound discussions and insights. Moreover, these digital assets offer educators the opportunity to integrate materials into classrooms or use them as supplementary resources that students can access remotely. (Adapted from “Digital Learning and Education in Museums – Innovative Approaches and Insights, 2023”) At the same time, OERs hold the power to transcend geographical and language barriers, making valuable resources available to a worldwide audience. With the incorporation of translations or subtitles, audiovisual content becomes accessible to learners from different language backgrounds. By sharing your AV collection, your institution is directly fostering collaborations and contributing to the benefits of society.

Allow educators to digitally create and organise lessons to use onsite and/or remotely

No matter which tool teachers employ to craft their educational exercises, the ability to share these resources proves advantageous for all parties involved. Imagine a teacher constructing a lesson on the Cold War, seeking to incorporate period-related videos. Scouring the internet, the teacher discovers numerous digital assets, and after establishing selection criteria, shortlists 10 videos. In support of the lesson, textual materials and images are also chosen. Following several hours of work, an engaging and captivating learning activity takes shape. The teacher is overjoyed with the outcome and wants to share it with fellow educators, enabling them to employ the same activity with their students. In the present day, fulfilling this aspiration is no longer an issue, thanks to various online options like the Historiana platform. By making your collection accessible, you’re also empowering educators to creatively assemble and distribute learning activities. Furthermore, the open licences connected with Open Educational Resources often permit the modification and adaptation of materials to align with specific educational contexts. Educators can customise content to match their students’ requirements, fostering an individualised and tailored learning journey. At the same time, your institution will foster use and engagement with your AV collection and create value to it.

Enlarge possibilities to share curated lessons facilitating the connection between the different materials

Sharing educational activities promotes open education. By making your collection accessible, you’re essentially making valuable materials available that might otherwise be underutilised. It means that, by sharing your collection you are also contributing to enhance the understanding of your collection in dialogue with other collections. OERs offer a host of benefits that can greatly enhance the capacity of audiovisual collection holders to share meticulously curated lessons alongside cross-references. Educators can cross-reference their lessons with specific materials from audiovisual collections. This integration of visuals and primary sources elevates the educational experience by providing learners with direct access to historical and cultural assets, fostering a deeper understanding of the subject matter.

Amplify cultural awareness and create space for marginalised students to have access to different cultural assets

We don’t need to delve deeply into the discourse on our society’s inherent inequality and unfair distribution of resources. However, by opening your collection to the public, you are actively contributing to a more equitable access to cultural heritage. One of the initial areas where disparities in access emerge is within the school system. While certain students possess financial means to acquire top-notch educational materials and explore museums and cultural venues, a significant portion of students lack the financial capacity for the same opportunities. Leveraging digital resources, educators could bridge the gap by introducing greater access to cultural content within classrooms. This approach has the potential to narrow the social divide among students, at the same time that your institution is directly contributing for the benefit of society.

Examples & initiatives

To give you some inspiration, we will describe two projects and initiatives that illustrate some of the reasons and added value you could benefit from, if you open your AV collections as OERs.

If you want to delve more in-depth into the opportunities of digital learning and education, you can find very insightful discussion in the most recent report published by NEMO: Digital Learning and Education in Museums – innovative approaches and insights.

ViCTOR-E

Brief description

ViCTOR-E was a research project which from 2019-2022 investigated how non-fiction cinema represented and shaped European societies after World War II. The idea was to develop a ‘transnational and multilingual’ collection in the format of e-learning exercises.

Presentation

e-learning packages with different content: texts, videos, photos (and comparison between images), maps, open questions, etc.

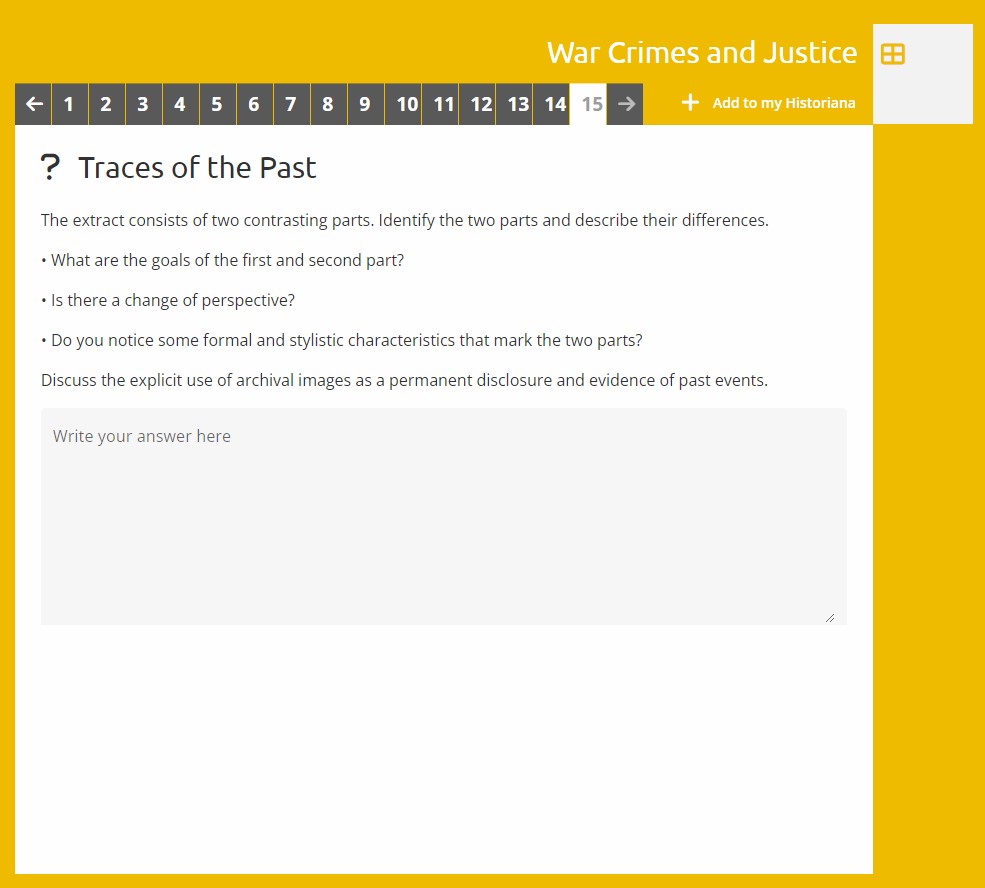

War Crimes and Justice

This e-learning package is hosted at Historiana and has open access to everyone who holds an Historiana account.

The content discusses traumatic events of WWII and attempts to do justice, positively affecting the victims and survivors of these events. The student has access to 15 cards, with each one discussing the theme and encouraging the reader to reflect on it. From introductory texts to specific examples of war crimes, the exercise invites the reader to reflect on the presented facts but also critically analyse the choices made in the moment the film extract was produced. Beyond the choice of discussing the historical events, the cards also aim to enhance critical thinking about the medium and ways in which the facts are presented.

Students can read texts explaining specific concepts. The material was created to promote reflection about the historical fact but also make connections with the current social context.

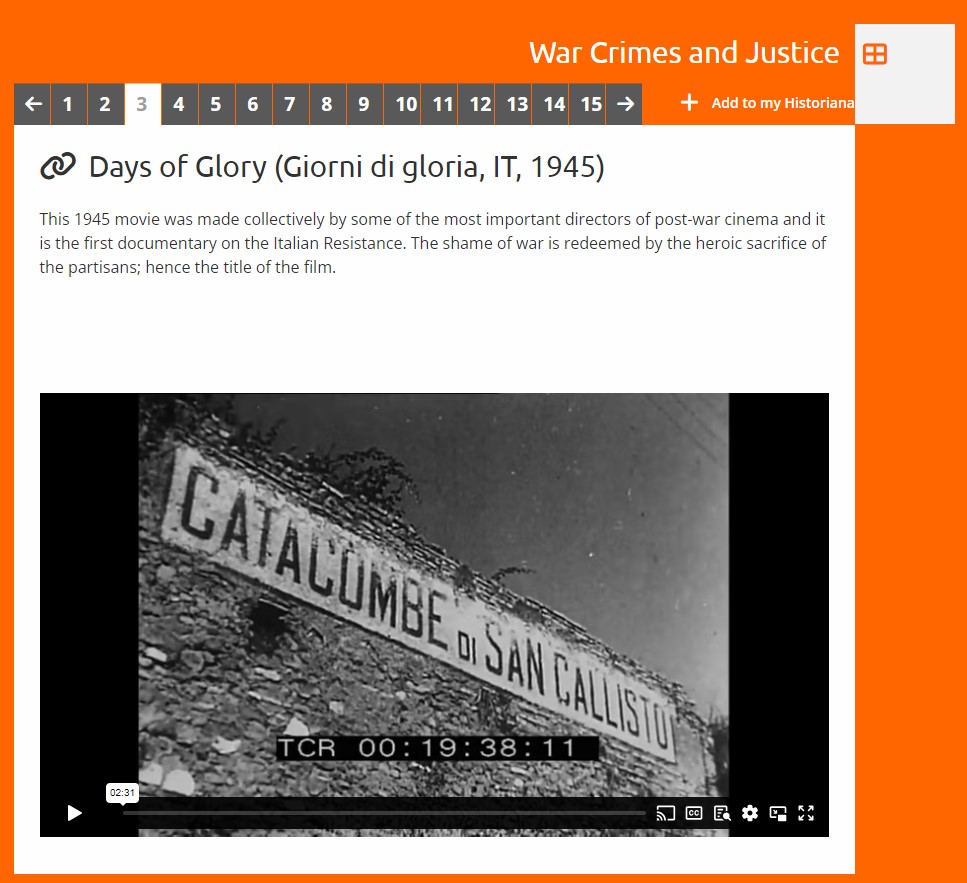

Video fragments are available for a more critical analysis. Students are asked to watch and reflect upon the content, as well as trying to understand the aesthetic choices made during the film production.

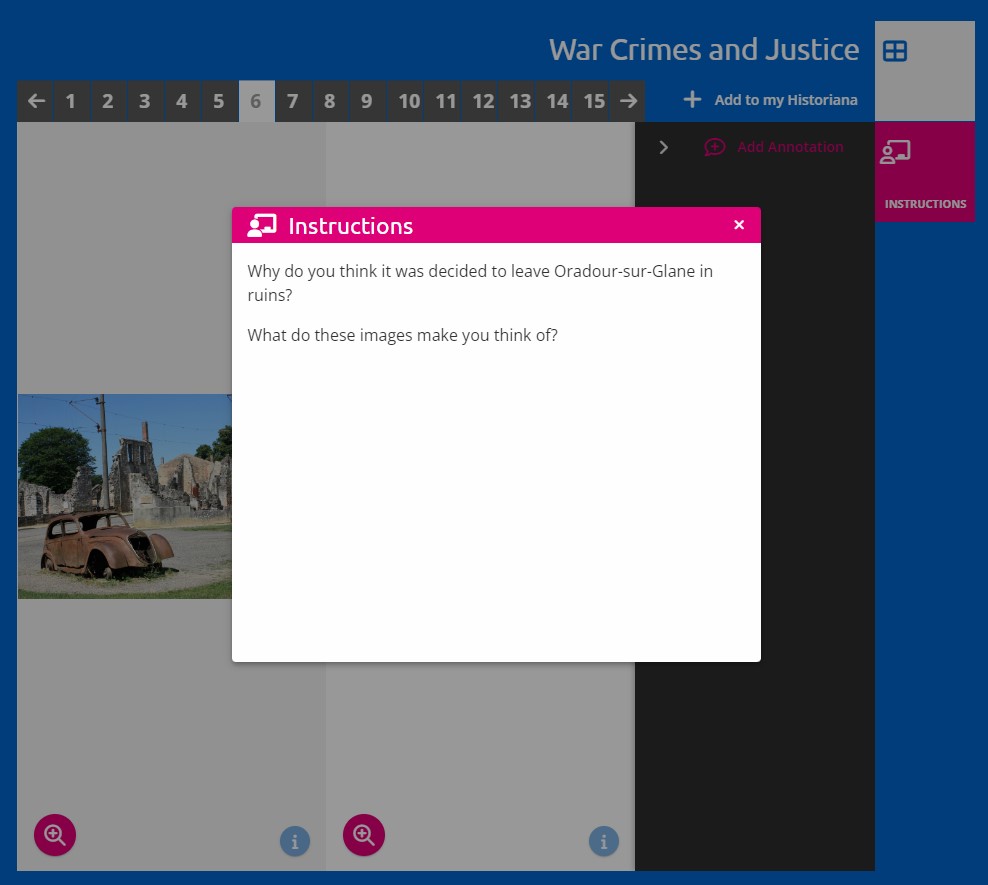

Images and other sorts of primary sources also are presented. Mostly, students are asked to investigate the hidden meanings.

Students are motivated to critically make connections between the different materials used in the lesson. After that they will send the answers to the teacher, who can assess the results of such material.

This example shows how the e-learning packages can help and complement the classroom discussions using OERs materials. The project also presents complementary background information for teachers to help adapt each lesson according to their own goals.

Benefits

By accessing all these different sources the students can deepen their understanding of a historical event and draw connections to contemporary issues. Simultaneously, this initiative sheds light on vital facets of the cultural heritage institution, increasing recognition for the organisation and giving access to important historical resources.

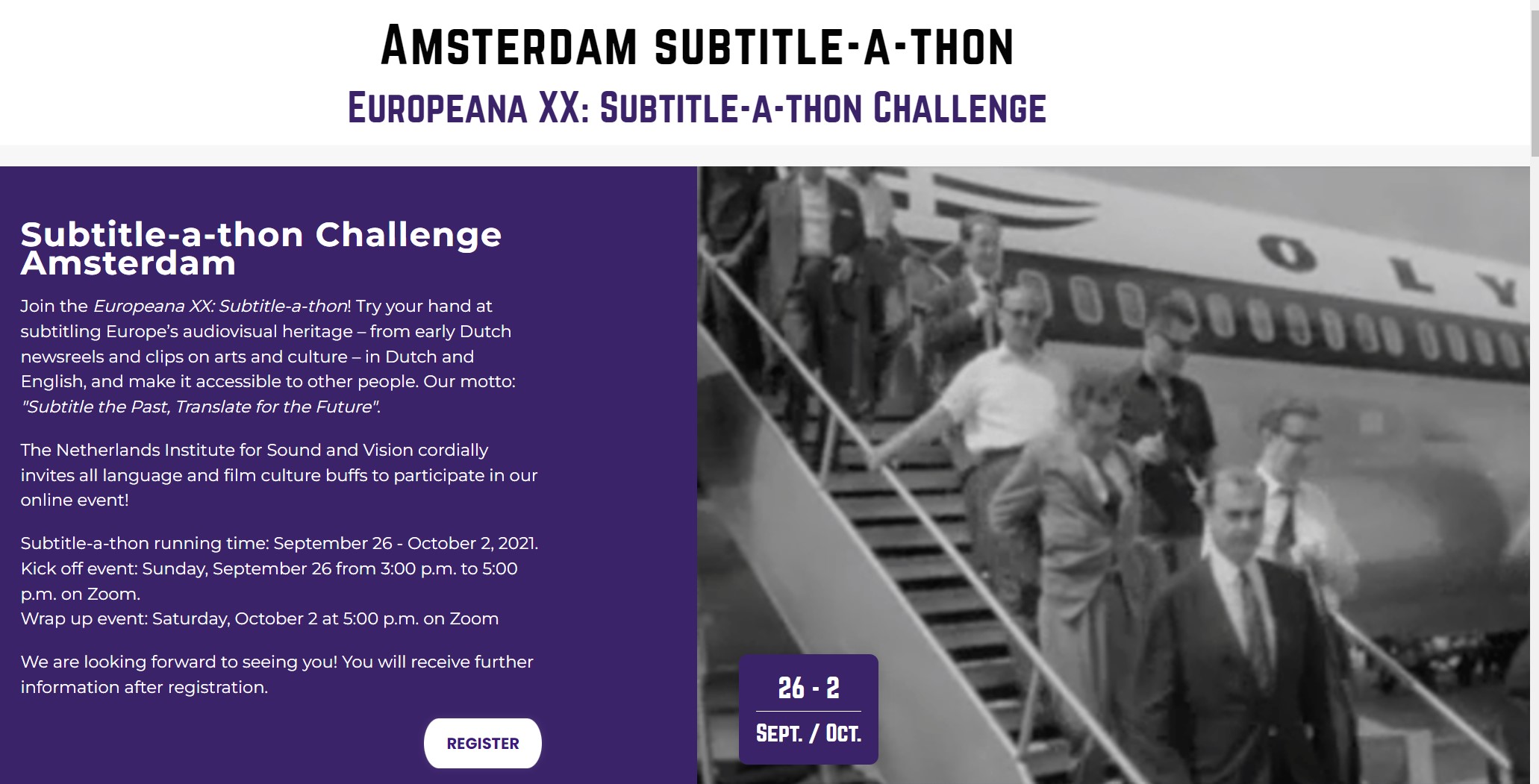

Subtitle-a-Thon

Brief description

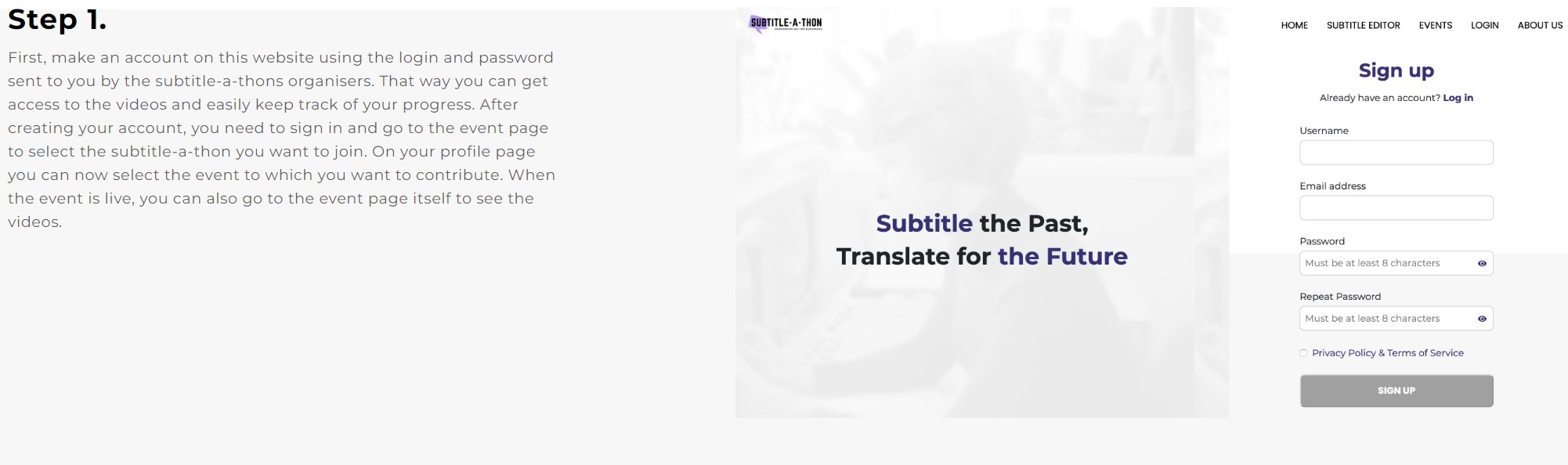

This initiative opened space for educators to motivate their students to create and add subtitles to archival media clips. Educators were invited to organise their own subtitle-a-thon events, curating video galleries and involving students in gamification activities. This initiative was also integrated into Content and Language Integrated Learning (CLIL), enabling students to utilise AV material within their second language learning process. Through this approach, students not only learned subtitle creation but also gained a deeper understanding of video content and enhanced their foreign language proficiency.

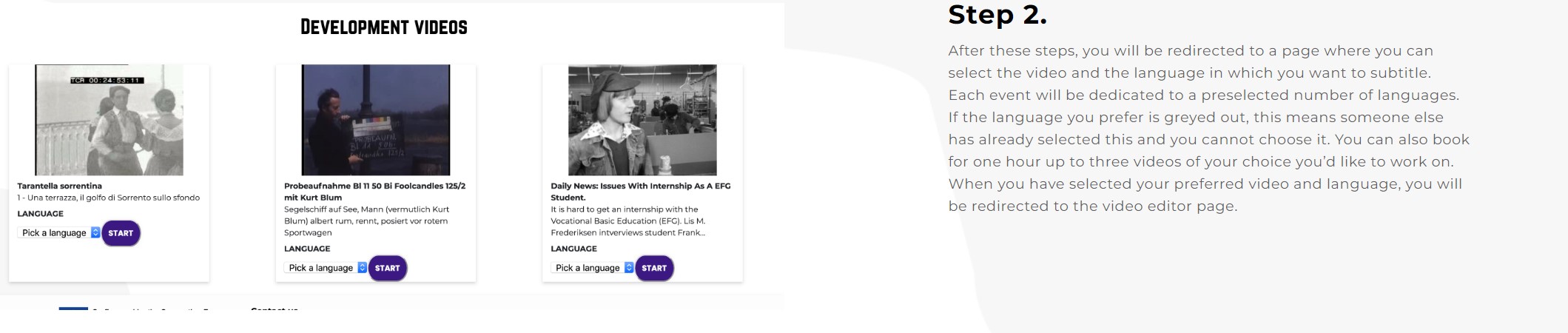

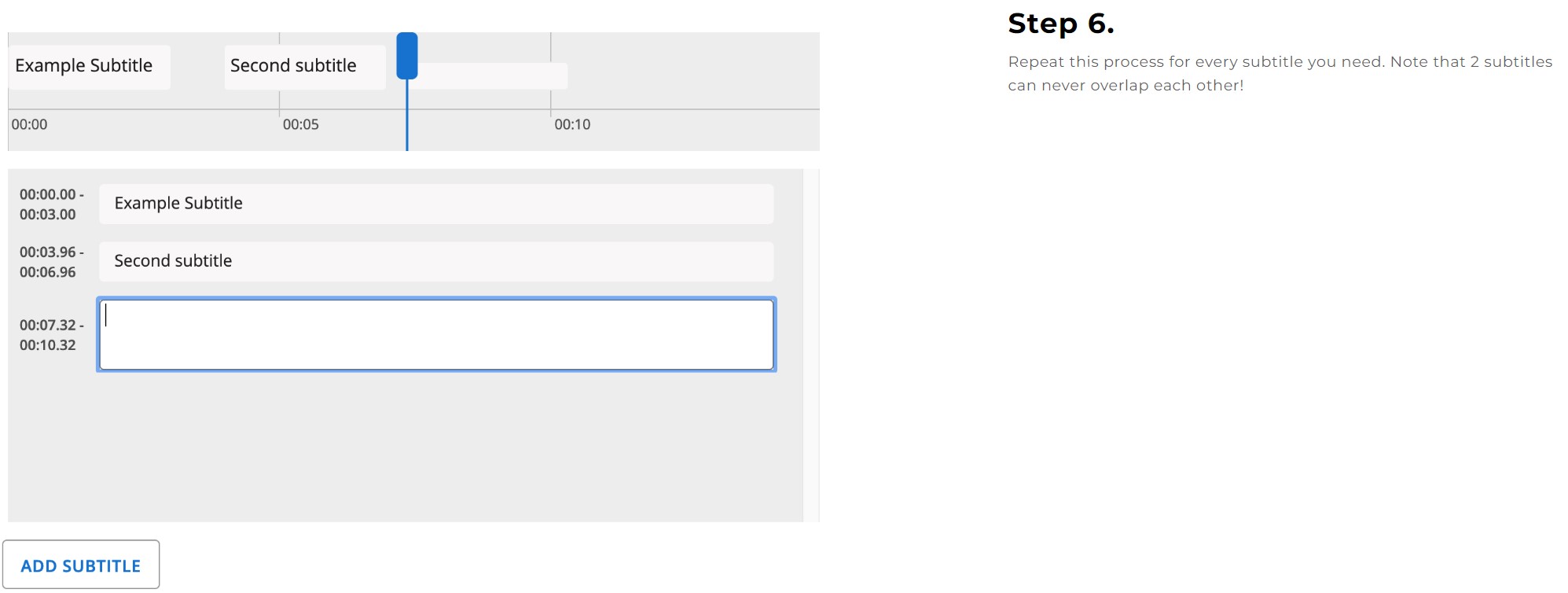

Presentation

An online platform in which educators could learn how to set up their own subtitle-a-thon events. At the same time, Europeana Initiative could enrich its collection through crowdsourcing activities.

The crowdsourcing events were organised in five different cities. They mobilised universities and schools to motivate their students in a gaming competition, learning how to subtitle videos and improving the students language skills.

Students were invited to watch short clips from the institution’s partners of the project, whose content is available on Europeana.eu. They would need to create subtitles, test their language skills, and share their experiences with other participants.

The platform offers tutorials to ensure that students can understand each step of the process and what was expected from them, at the same time learn new skills and develop critical thinking about the process of subtitling videos.

Benefits

By accessing all these different sources the students could acquire knowledge on the content of the videos they were subtitling. These materials would later be used in lessons for different subjects. Moreover, students could immersively improve their language skills.

Simultaneously, the institutions could increase the number of AV material with subtitles and/or closed captions digitally available.

Needs & Wishes - educators and AV collection holders

Educators’ needs and wish list

In a research conducted by MARE – Diane Stenhaus-Karelse (Research Director) and Shari Kok (Research Manager), the Netherland Institute for Sound & Vision surveyed education experts and teachers from different educational levels in the Netherlands. The results of the survey showed that:

AV material greatly contributes to the transfer of knowledge and to achieve learning objectives

There is a lot of AV material available online, but searching and organising these materials is time consuming

Different target groups (educational level) require different application of the AV material

The use of established education platforms can help teachers find the AV material that better fits their goals

In the realm of education, the integration of audiovisual (AV) collections has become a pivotal tool for enhancing the teaching and learning experience. We present below the perspective of educators who are eager to harness the potential of AV collections. By highlighting the value of AV content and addressing the specific needs of educators, this section aims to outline a wish list that showcases educators’ aspirations and requirements when it comes to utilising AV collections effectively.

Relevance and Quality

Educators seek AV collections that are not only up-to-date but also of high quality, which means content that aligns with current curriculum standards and offers accurate information, as indicated by the educators.

Embeddable Content

Educators also wish for the ability to seamlessly embed AV content within their lessons and presentations, where a simple click integrates a video or audio clip into their teaching materials, eliminating the need to switch between platforms.

Ease of Navigation

Navigating AV collections can be overwhelming. Educators wish for user-friendly platforms that offer effective search filters tailored to educational needs. The ability to search by topic, grade level, and educational relevance would be beneficial.

Customization and Adaptability

Educators want to modify AV content to align with their class. This includes the ability to edit videos for specific sections, add subtitles for language support, and create content playlists that suit different classes.

Educational Collaboration

Educators value platforms that enable collaboration and information sharing among peers. One of their wishes is to have a forum where educators can exchange insights, review AV content, and offer recommendations.

Longevity and Accessibility

The longevity of AV content is vital. Educators wish for content to remain accessible and functional over time, even as curriculum and teaching approaches evolve.

Incorporating Interactivity

Educators desire AV content that encourages interactivity. This includes videos with built-in quizzes, interactive simulations, and opportunities for students to respond and engage actively with the material.

AV collection holders’ needs & wishes

And I would like to be able to rearrange and improve my own display [referring to the institutional platform]. [In our institution] we are quite close to an optimal display, but the website is separated from the collection [database]. Those are two separate websites, and this is inconvenient. We are stuck with the website design and the way it was created. [I wish] the website could be more uncluttered, [bringing an overview of what we have in-house].

– Education Specialist at a Dutch Cultural Heritage Institution

We would like to share five insights collected from interviews with cultural heritage experts that express their wish list in relation to sharing AV collection as OERs. Through enhancing their existing initiatives, they aim to deliver significant advantages to the field of education.

WISHES

SO THAT

EXPECTED RESULTS

Expand and strengthen collaboration with higher education

Cultural institutions can embrace students’ knowledge to create new educational materials to use in classrooms

- Increase the number of educational materials available

- Enhance educational materials

Better performance of the database

Teachers can easily access AV materials

- More AV material can be found and selected

- Teachers spend less time trying to figure out how the search machine works

Increase visibility of existing learning materials

More teachers can access, use and improve these materials

- The use of AV collections would be facilitated

- Possibilities to share AV collection would increase

Better understanding of the impact of AV collection in educational settings

CHIs can increase and improve the materials available as OERs

- CHIs can use the results of impact assessment to understand the value of their own collection

- The more information CHIs have about the impact of their actions, the more effectively they can plan upcoming activities

Better collaboration between film industry and education

Producers and distributors can better understand the importance of sharing AV materials as OERs

- Increase in the number of AV materials available for educational (re)use

- More students can benefit from the variety of learning materials

AV collection & Education - from the field to the field

This chapter offers guidelines for AV collection holders to open up the collection as Open Education Resources (OERs). This section draws from best practices and insights gathered from experts in the AV field on how they have worked to make their collection available and promoted access to the collection.

Steps to open up AV collections for education (re)use

The following steps will help you open up your AV collections for educational (re)use:

- Strengthen your institutional connection with schools/educators

- List the collection items that are free to use (public domain)

- Ensure that the material is digitally available

- Review & Improve the collection’s metadata

- Provide closed caption and/or subtitles

- Find solutions for the limitations you can face

- Enrich the AV collection with extra features

- Present the AV collection digitally and attractively

- Assess the impact of your actions

1. Strengthen your institutional connection with schools/educators

In order to create good material and resources for educational purposes, it is important to first know how teachers want to use audiovisual materials in classrooms and how the curriculum is being taught in practice.

Then I think, okay, if one teacher asks for this then I bet there are a hundred other teachers who want this too!

– Education Specialist at a Dutch Cultural Heritage Institution

There are several ways in which you can get this information from teachers:

- Organise focus groups with teachers;

- Contact teachers via trade unions;

- Contact teachers via groups on social media platforms, such as Facebook (see the box below);

- Contact teachers via mailing list.

In some cases, schools find their way to you and ask for specific audiovisual materials. In that case, you can provide them with the required material and then distribute it to more teachers within your network.

Things to keep in mind in order to open up AV-collections for educational purposes

Once you’ve reached out to schools and educators to gain insights into their material and subject requirements, you’ll be able to consider specific audiovisual materials that align with the educational and pedagogical needs of the teachers. However, if you feel like needing a more comprehensive understanding of your own collection, delivering the best content to educators becomes a challenge. We’ve compiled a brief checklist of factors to consider as you move forward with the goal of making your collection accessible for educational purposes.

2. List the collection items that are free to use (public domain)

Inventory of the material available in your collection with a clear indication of rights holders and copyrights issues.

We understand that holding a very good understanding of your institutional collections is quite a demanding task. Regardless of the size of your institution, there will always be items within the collection that lack clear information about provenance and copyright. Unfortunately, a miraculous solution isn’t available in this scenario. The initial step you must take in the direction of sharing your audiovisual collection as Open Educational Resources (OERs) involves creating a precise inventory of the materials you have in your archive. This includes identifying rights holders and specific directions about the ways the materials can be used by the public. A list of materials in public domain (CC0) or under other licences such as CC BY, CC BY-SA, CC BY-NC would help you to make a first selection.

Check chapter 5 to learn more details about copyright.

3. Ensure that the material is digitally available

Ensuring that the collection is digitised helps identify which material you can offer for education purposes.

We’ve received feedback from experts in the field indicating that the digitization process can be a big challenge, primarily because collection holders often face obstacles in fully digitising their entire collection, including insufficient human resources, inadequate equipment, financial constraints, among other barriers. While ensuring the digital accessibility of your AV collection is essential, the good news is: there are various avenues for securing funding and guidelines to support the digitization of collections and the broader digital transformation. If the process of digitising your collection seems difficult, the examples provided below might inspire you to embark on this journey.

Digital Europe Programme: is a European Union (EU) initiative aimed at advancing the digital transformation of Europe’s societies and economies. The program is designed to ensure that all citizens and businesses can benefit from the digital revolution.

Horizon Europe: the successor to Horizon 2020, continues to support research and innovation projects related to cultural heritage digitization until 2027. It promotes collaborations between CHIs, research institutions, and technology providers to advance digitization techniques and tools.

Creative Europe: is the EU’s program for the cultural and creative sectors. While it primarily supports the audiovisual and creative industries, it occasionally funds projects that involve digitization, preservation, and access to cultural heritage.

Europeana Initiative: a key initiative supported by the EU to enhance digital access to Europe’s cultural heritage and raise public awareness of its diverse cultural resources. Their network of aggregators support cultural heritage institutions throughout Europe to digitise and share their collections.

4. Review & Improve the collection’s metadata

Good metadata simplifies the process of retrieving information and promotes content discoverability.

Digitising your collection and making it available includes the necessity of mandatory metadata. Regardless of the platform you select for showcasing your collection, it’s essential to provide details about the object (e.g. video, audio). Online resources like Dublin Core elements, EBU Core metadata set, and Europeana Data Model (EDM) offer various options for mandatory and recommended metadata. However, we have curated a short list, aligned with EDM, encompassing the most frequently utilised metadata elements.

In this simplified table, the three EDM core classes are presented and briefly described, but you can find more details at Europeana Knowledge Base.

Cultural Heritage Object

Title

It is a name given to the object

Description

It provides a description of the object

Type

It provides the nature or genre of the object, “ideally the term(s) will be taken from a controlled vocabulary” (text, video, sound, image, 3D)

Language

It describes the language present in the object (text, sound)

Spatial

It provides the spatial characteristics of the object, i.e. what the object represents or depicts in terms of space (e.g. a location, coordinate or place)

Temporal

It is about what the object depicts in terms of time (e.g. a period, date or date range)

Aggregation

(makes the link between the cultural heritage object & the digital object representation)

Provider

It provides the name or identifier of the provider of the object (i.e. the organisation providing data)

Data provider

It is the name or identifier of the data provider of the object (i.e. the organisation providing data to an aggregator)

isShownAt

It is the URL of a web view of the object in full information context

isShownBy

It is the URL of a web view of the object

Rights

It provides the rights statement that applies to the digital representation of an object (you can find more details HERE)

5. Provide closed caption and/or subtitles

The lack of subtitles can be a barrier in terms of access and inclusion. The use of closed captions and subtitles ensure that videos are accessible to students with hearing impairments, creating an inclusive learning environment for all students.

... if there are no subtitles, it becomes challenging for individuals with hearing loss.

– Education Specialist at a Dutch Cultural Heritage Institution

Using closed captions and subtitles in different languages on videos offers several benefits that enhance accessibility, learning outcomes, and engagement. For example, the use of subtitles in multiple languages helps language learners by providing written text alongside spoken language. It also facilitates multilingual education by providing translations and/or bilingual content. Captions and subtitles add comprehension layers, especially for complex topics, as students can read along while listening.

In this simplified table, the three EDM core classes are presented and briefly described, but you can find more details at Europeana Knowledge Base.

We know, however, that archival materials hardly come with closed captions/subtitles. To solve this problem we suggest that you develop projects for using crowdsourcing events/activities, in collaboration with educators, to enrich your AV collection.

Earlier in this guide we presented examples of how you can use crowdsourcing activities to widen the range of subtitles available with the video extract → Subtitle-a-thon

6. Find solutions for the limitations you can face

The selection and sharing process may not always proceed without facing challenges and difficulties. The solution to overcoming these challenges depends on the specific problem and its scope.

In the table below, we outline common challenges that you may face when sharing your AV collection as OERs and provide potential solutions for them.

LIMITATION

DESCRIPTION

SOLUTION

Difficulties in selection

Size of archive: archives typically hold extensive collections that cannot be fully processed due to their immensity.

Too large AV-files: archives also struggle to manage large files that may not be suitable for internet usage.

Sometimes the solution is simpler than what we expect. To deal with these problems you might create a list of criteria. These criteria should be clear and give indications about what makes a specific item worth a more in-depth investigation. Using the collection’s metadata create a priority list of objects that could be interesting for education use (e.g. the content has clear reference to a historical fact).

External dependency

In addition to the challenges mentioned earlier, we can pinpoint two extra factors that might hold you back from sharing AV collections as Open Educational Resources (OERs).

- Access depends on distributor

- Families don’t give public access to material

Both situations depend on external parties and it’s not always possible to overcome these impediments. However, we would like to present you three options that might help you identify how you can tackle these challenges.

Option 1: you can work in a bulk to make all AV collections open for educational use and registered under educational copyright labels (more details here). This means that you would not depend on distributors or right holders to make available items from your AV collection.

Option 2: you could also decide to partially keep items not accessible. For that, you might have a detailed list of requirements to guide you in your selection. Afterwards, take the necessary steps to apply an educational copyright label.

Option 3: although this might sound frustrating, in some cases you just need to accept that part of your collection will not be freely open for educational purposes, whether due to distributor restrictions or due to family disagreement.

Sensitive material

In contemporary discourse, the conversation surrounding colonialism and sensitive material has gained emphasis. The discussion has highlighted the necessity of critically analysing historical artefacts, documents, and media and recognizing their potential to perpetuate biassed narratives and prejudiced imagery. As society deals with the legacy of colonialism, there is a growing awareness of the need to acknowledge, contextualise, and reevaluate such materials. By engaging in open discussions and responsible curation, there is a collective effort to navigate these issues while fostering understanding, empathy, and historical accuracy.

At this point, we would very much like to present a clear solution, but this subject is surrounded by strong feelings and different perspectives. To tackle the issue of sensitive material in your collection, we would suggested that:

- Dare to be critical and acknowledge that your institution holds bias and sensitive material. By doing so you are taking the first step toward finding solutions.

- We believe that archives and other cultural heritage institutions should not act as gatekeepers but as facilitators. It means that the decision of using such materials should not rely on the institution’s hands. However, we strongly advise that any material that might be harmful for some individuals or groups should be accompanied by a disclaimer making it clear that the content, language and metadata can be biassed.

If you have an old fragment about the celebration of Keti Koti in Suriname where terms like 'Creolen' or the n-word are used, then you start to wonder if you should or not make that material available. You cannot modify the [original] language. And sometimes it is also in the metadata. [Perhaps] you can adjust a small portion of a fragment, but not for the entire program [the film]. In our institution we are deeply engaged with this discussion. We're considering whether we should implement a general disclaimer. It's also a reflection of the prevailing attitudes of the time.

– Education Specialist at a Dutch Cultural Heritage Institution

7. Enrich the AV collection with extra features

Once the materials suitable for educational use have been chosen, it is crucial to assess them against indicators aimed at enhancing media literacy. Likewise, it is important to reflect on the source itself (creator, purpose, message), but also to reflect on other materials that shine a different light on the issue or event.

And also, if you talk about a multi-perspective... they said 'yes, we know that, but we only know American films of Vietnam. We don't have any Vietnamese films about it.

– Education Specialist at a Dutch Cultural Heritage Institution

The table below presents some extra features that could be helpful for educators and students to deepen their understanding of the AV material used in class. Although most of these extra features would be taken into account during the lessons preparation (by the educators) and/or students analises, it is important for AV collection holders to keep them in mind, so that other written materials and/or AV materials can be presented together and enrich the learning experience.

MEDIA LITERACY FEATURES

FEATURES TO FACILITATE SOURCE CRITICISM

Reliability of portrayed event or person

In essence, portraying events and persons with different nuances in historical audiovisual material is an ethical and educational imperative. When doing this, you will contribute to a more diverse collective memory. Additionally, reliable portrayals show respect for the people who lived through historical events and for the importance of those events themselves.

In case not everything in the material is a good representation of the event or shows just one side of the story, this could be an opportunity to further discuss with students. EuroClio offers a good example with the Teaching practice “Was the Glorious Revolution really ‘glorious’?”.

Multiple perspectives

The importance of incorporating multiple perspectives when learning history cannot be overstated. History is not a singular narrative; rather, it is a complex narrative from diverse experiences, viewpoints, and interpretations. Embracing multiple perspectives enriches our understanding by presenting a more holistic and nuanced portrayal of past events. By examining history through different lenses, learners gain a broader awareness of the complexities, motivations, and consequences that shaped various historical moments. This approach fosters critical thinking, empathy, and a nuanced understanding of the human experience. It also encourages students to question assumptions, challenge biases, and recognize the subjectivity, multiplicity and polyvocality in historical accounts.

Given these factors, it makes sense to choose audiovisual materials that encompass multiple perspectives and collaborate to elevate the discourse.

Course of action

Certain historical and citizenship-related topics call for a distinct approach. When addressing themes like injustice and abuse, a specific degree of what can be termed a “course of action” becomes essential. In this context, “course of action” refers to the presence of a perspective within the film that motivates viewers to take action. Additionally, when films include concrete behavioural cues, it becomes considerably easier for individuals to initiate the first steps toward action.

This notion emerged from a collaborative research project conducted by ‘Movies that Matter,’ a Dutch film festival dedicated to human rights and human dignity films, in partnership with Erasmus University. During the impact research, a framework was established to define the intended outcomes of films. This framework considered key social indicators such as empathy, tolerance, social trust, and altruism. These indicators were assessed using scales before and after students watched the films. The findings revealed that films exhibiting a significant “course of action” element were more likely to yield higher scores on these social indicators among students.

Positionality in history

Positionality in history refers to the recognition that our understanding of historical events is influenced by our own individual perspectives, biases, and experiences. It acknowledges that no historical account is entirely objective, as anyone that is in contact with the materials brings their unique backgrounds, cultural contexts, and personal beliefs to the interpretation of historical narratives. Positionality brings us to critically examine how our own identities and perspectives shape the way we perceive, select, document, archive, and interpret historical events.

Incorporating positionality into the analysis of AV materials encourages a more nuanced and comprehensive understanding of the past. It encourages us to consider the voices and experiences that may have been marginalised or overlooked in traditional narratives. Embracing positionality also encourages empathy, as it prompts us to explore history from different angles, fostering a deeper appreciation for the diversity of human experiences throughout time.

Written resources that complements the content of the film/video

As previously noted, audiovisual material possesses a potent ability to convey messages independently. However, textual content can introduce an additional layer of depth and enhance comprehension of the visual elements.

A compelling illustration of this principle can be found in the practices of the ‘Rotterdams Stadsarchief‘, an archive situated in Rotterdam. This institution gathers diverse historical materials, encompassing films, photographs, newspapers, and drawings. During instructional sessions involving photographic and moving imagery, they occasionally utilise newspapers to exemplify the discourse surrounding specific subjects. This approach can contribute an extra dimension to your audiovisual content.

Another example comes from the Historiana platform. In the lesson titled “Men and Women at Work” a collection of supplementary texts accompanies the videos and photographs.

Source criticism

Source criticism is a critical skill in evaluating the reliability and context of historical sources, including audiovisual (AV) materials. When dealing with AV materials, such as videos, documentaries, or multimedia presentations, source criticism becomes especially important due to the potential for manipulation, bias, and misinterpretation that can occur through visual elements.

Therefore, it is important for educators to incorporate source criticism when using AV materials in educational settings. It involves asking questions about the origin, purpose, and potential biases of the content. Educators and students should consider factors such as the creator’s intentions, the historical context in which the material was produced, the influence of audio and any potential alterations or editing that may have occurred.

All these different nuances should be available together with the source (AV material), giving the opportunity for educators and students to ask critical questions about the source and content.

Short fragments that are easily to implement in class

Short video fragments offer a convenient and efficient way to enhance classroom learning. Their concise nature allows educators to focus on specific concepts, themes, or events without overwhelming students with lengthy content. By selecting key segments, teachers can tailor the learning experience to suit their lesson objectives, ensuring that the material remains engaging and relevant. This approach also provides flexibility, as educators can seamlessly integrate these video fragments into their teaching plans, sparking discussions, analysis, and critical thinking among students.

Incorporating short video fragments into classroom instruction not only captures students’ attention but also encourages active participation. These snippets distil complex ideas into bite-sized portions, making them more accessible and comprehensible for learners of all levels. The visual and auditory components of videos engage multiple senses, aiding in information retention and knowledge assimilation. Teachers can strategically intersperse these video fragments throughout their lessons, creating dynamic teaching moments that stimulate curiosity and foster a deeper understanding of the subject matter. Additionally, the brevity of these clips allows educators to prompt discussions, reflections, and collaborative activities that capitalise on the immediacy and impact of visual content.

Reflection on provenance

Also as a means to enhance source criticism, provenance refers to the origin, history, and chain of custody of an object or artefact, including its ownership, custody, and exhibition history. In the context of audiovisual (AV) material, provenance can have a significant impact on the analysis of the content. By offering additional details regarding the provenance of the collection, educators and students can delve into richer discussions and gain a deeper comprehension of the contextual origins of the audiovisual fragments they are utilising.

When discussing history education, it's crucial to consider the concept of "positionality", a well-established term in history teaching. This concept can also be applied effectively to the study of film, simplifying the instructional approach. In doing so, there’s no need to create distinct teaching methods.

– Education Specialist at a Dutch Cultural Heritage Institution

Why is it important to use AV material in history educational settings?

Incorporating audiovisual (AV) material into history educational settings holds profound significance for fostering engaging and comprehensive learning experiences. AV content, including historical videos, documentaries, and multimedia resources, offers students a dynamic and immersive way to connect with past events and narratives. By visually and audibly engaging with historical contexts, students can develop a deeper understanding of the complexities, emotions, and perspectives that shape historical moments. AV material also breathes life into subjects, making them more relatable and resonant, enabling students to develop a more empathetic connection to the past. Additionally, the inclusion of AV material promotes critical thinking as students analyse visual cues, audio narration, and other elements, honing their skills of interpretation and evaluation. Ultimately, the integration of AV resources enriches history education, providing students with a multi-dimensional learning experience that bridges the gap between text-based learning and the vibrant realities of history.

AV-collections help students to understand (historical) facts better and can improve their social skills, because:

A. Visuals are a primal way of learning

Much research has been done on the influence of images on learning processes over the years. In science, there is the concept of ‘Pictorial Superiority Effect’, which refers to a cognitive phenomenon that suggests that people tend to remember images and pictures better than words or texts. In other words, when information is presented in both visual and verbal formats, individuals are more likely to recall and retain the information presented in the visual format (images) compared to the verbal format (words). In this way, imagery enhances the memorability and engagement of learning, serving as prompts for critical thinking and discussions in the classrooms.

We live in a visual culture. So these kids are much more visual, more visually oriented. But if they have an image of something to that, it is easier to link to the lesson material.

– Education Specialist at a Dutch Cultural Heritage Institution

Example

The initiative Centropa offers a good example of how to make available AV resources which provide historical themes and extra materials to guide teachers and students in their journey through history. When searching in their system, you can find a list of themes from which you can select specific materials to download and/or watch online. Let’s take a look at one example and understand how you can give access to your AV collection and ensure users will have the best experience possible from using your collection: Maps, Central Europe and History.

While it might appear to entail a substantial amount of effort, the process essentially involves arranging the existing information within your collection and presenting it alongside the audiovisual content.

How to highlight items from your collection in practical terms:

- List of topics and themes covered by your AV collection;

- Clear description of the material and connections with the historical subject;

- Link to download video/audio;

- Link to download subtitles;

- Link to download important metadata and other information related to your AV material;

- Related resources (materials that are connected to the item in question)

- Space for public participation: share stories, share studying materials etc.

B. AV collection help to explain a historical event

You can use your AV-collection in order to explain certain historical events or concepts. For example, imagine that you have in your collection a special video/audio that clearly describes a period in history and you think this material could be useful for educational purposes. You already researched the context, you know the topic very well and you want to help educators to engage the students in a learning journey full of creative experiences. Then you might consider giving a more in-depth access to your collection.

So, in that sense you can really connect with the class that you think it helps. And you can also say: ‘watch the clip again as a preparation for a lesson and then come back to it in class. Who can tell me about it?’ So then you start reflecting on such an excerpt.

– Education Specialist at a Dutch Cultural Heritage Institution

Example

The IWitness project shows how the use of testimonies can enhance the learning of historical facts. Developed by the University of Southern California Shoah Foundation, IWitness offers a platform that connects students and educators with video-testimonies from survivors and witnesses of significant historical events, notably the Holocaust. The platform offers a vast repository of testimonies, resources for educators and sets of online and offline student’s learning activities.

How to offer testimony and oral history for education use:

- List of themes existing in your AV collection;

- Selection of the material that presents relevance to historical themes;

- Digitise short fragments that could be used in education;

- Co-related material that enriches the testimonies;

- Make available a list of subjects and material for educators and students.

C. AV collections offer a way to discuss current affairs or bigger concepts

History is not only useful for a better understanding of our past, but also provides an opportunity to understand complex social issues and contemporary affairs. AV materials can serve as powerful tools for discussing current affairs and larger phenomena by providing visual context that engages learners on multiple levels.

If you are showing material about war and propaganda, then of course you are also talking about current affairs by asking questions like: 'Is this still relevant? Which current media channel do you believe in or not? And why not?’ If You can bring it to the now, it's easier to identify with the subject.

– Education Specialist at a Dutch Cultural Heritage Institution

Example

The initiative House of European History invites visitors on a journey through the history of Europe. Besides the space open for visitation, the initiative offers resources for educators, including prepared activities to use in classrooms. The activity “Borders and Bridges – Migration, for example, discusses the issue of migration as a historic fact with clear link to current migration issues.

How to offer historic material and make a link with current issues:

- List of themes existing in your AV collection that offers clear relevance to contemporary issues;

- Map all sort of material related to the subject, from different times in history;

- Digitise short fragments that could be used in education;

- Make available PDF with extra information about the subject;

- Link to download audio/video transcriptions;

- Offer a list of extra resources teachers can find elsewhere;

- Describe the theme, the material available, the students age etc.

8. Present the AV collection digitally and attractively

As important as considering the AV material available and the diverse aspects about the collection, how to present is crucial to increase critical engagement.

Opting for the most suitable platform for sharing your AV collection can expand its reach and enhance collection management. A number of different aspects might be considered when choosing the right platform for your institution, from the size of your collection to the types of materials, to the facility end users experience to find your material. Additionally, when selecting an educational platform for making the AV collection accessible, it’s beneficial to explore existing platforms designed for creating and sharing teaching and learning materials. Below, we offer some examples of digital platforms for aggregating cultural heritage collections and for creating and sharing educational materials. Keep in mind that there may be other options that are better suited to your specific requirements.

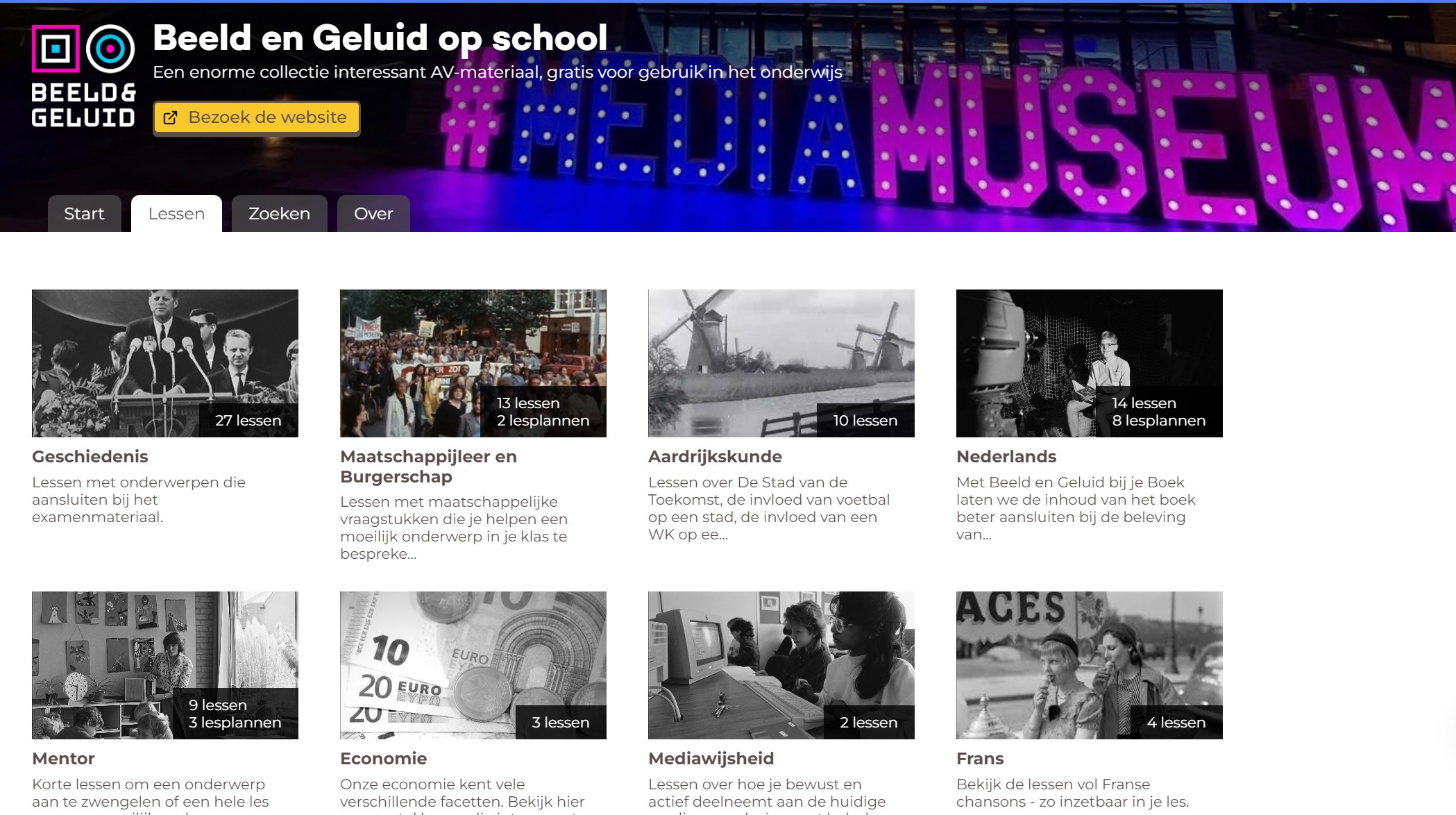

Digital platform to aggregate and find AV material

Europeana Foundation

Europeana Platform provides access to millions of cultural heritage items from European museums, galleries, libraries, and archives. It serves as a digital repository of Europe’s cultural treasures, offering a wide range of materials such as images, artworks, documents, videos, and audio recordings. The Europeana Initiative aggregates and makes available content from various cultural institutions across Europe, allowing users to explore and discover a diverse array of historical, artistic, and educational resources. Users can search Europeana’s vast collection by keywords, topics, time periods, and more. The platform not only provides access to individual items but also supports the exploration of thematic collections and curated exhibitions. It aims to promote cultural exchange, education, and creativity by offering a wealth of resources for researchers, educators, students, and the general public.

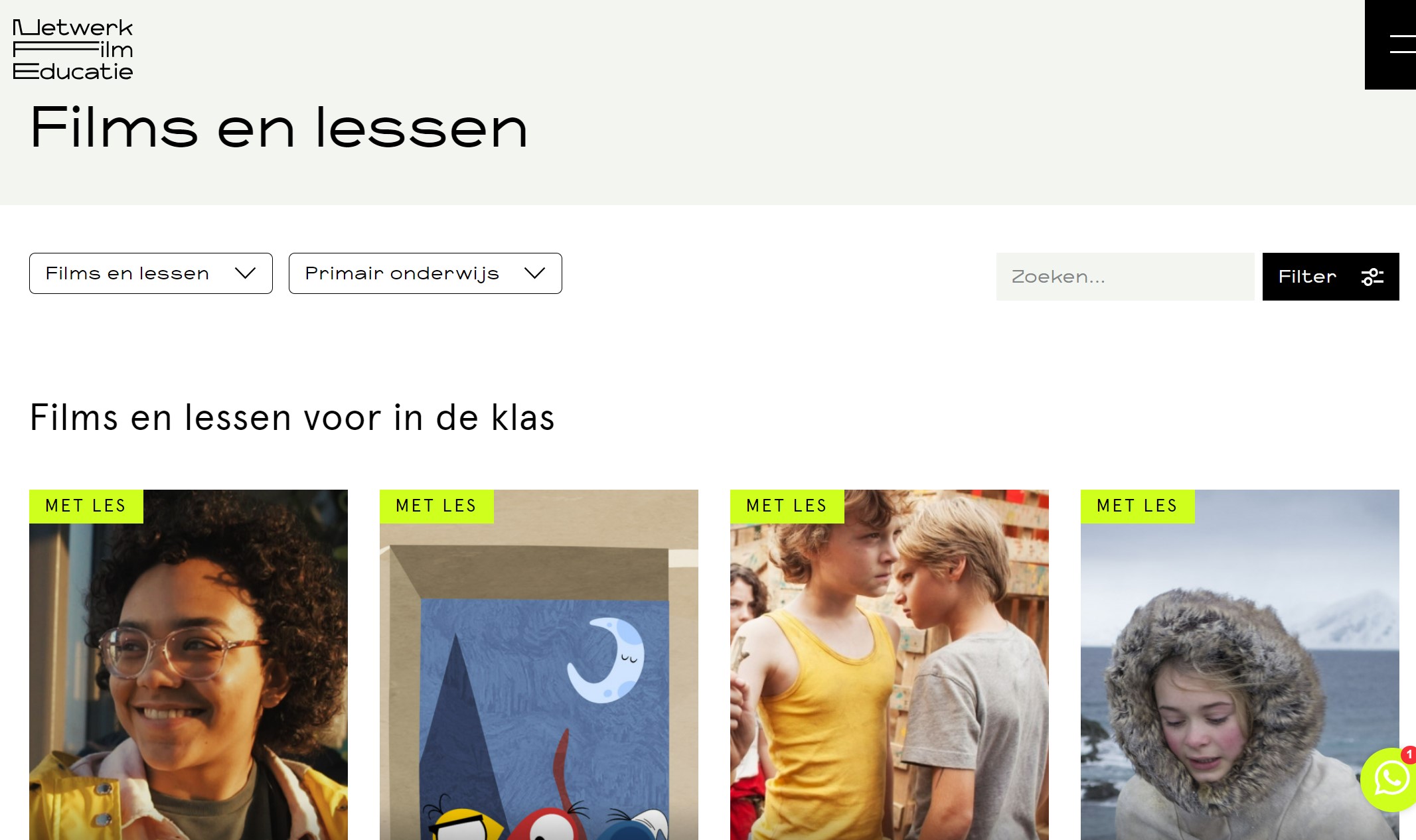

Netwerk Filmeducatie

Netwerk Filmeducatie is a platform that uses the expertise of CHIs to teach Dutch students how to speak the language of film. It provides a large film database for education, workshops and professional development.

Digital platform to create and share teaching and learning materials

Lesson-Up

LessonUp is a digital educational platform designed to support teachers in creating, sharing, and delivering interactive lessons and learning materials. It offers a user-friendly interface that allows educators to develop engaging lesson content using a variety of multimedia elements, such as videos, images, quizzes, and interactive exercises. Teachers can also access a library of pre-made lessons and collaborate with colleagues to enhance their teaching strategies. LessonUp aims to make teaching more dynamic and effective by enabling educators to craft interactive and visually appealing lessons that cater to the diverse needs of modern learners.

Historiana

Historiana is an online educational platform developed by EUROCLIO, the European Association of History Educators. It provides history teachers and students with access to a wealth of historical resources, interactive learning materials, and tools to create and share history lessons. Historiana offers a wide range of primary and secondary sources, such as images, documents, maps, and videos, covering various historical periods and topics. Teachers can use these resources to design engaging lessons that promote critical thinking and historical inquiry. The platform also encourages collaborative learning and allows educators to share their lessons and learning activities with others. Historiana aims to enhance history education by providing educators and students with an immersive and interactive platform to explore and learn about history.

9. Assess the impact of your actions

Impact assessment is a crucial tool for evaluating the effectiveness and outcomes of cultural heritage educational activities, including educational activities and the use of AV collection as OERs.

In the cultural heritage sector, educational initiatives are designed to engage learners, promote understanding of history and heritage, and foster a sense of connection to the past. Impact assessment provides a structured framework to measure the extent to which these goals are achieved and to uncover the broader social, cultural, and educational effects of such activities.

By conducting impact assessments, you as an AV collection holder can gain valuable insights into the effectiveness of the educational programmes. This involves evaluating not only the knowledge gained by participants but also the emotional and transformative experiences they undergo. Impact assessment helps institutions understand the long-term effects of their efforts on learners’ attitudes, behaviour, and engagement with cultural heritage. Additionally, these assessments provide evidence of the value of cultural heritage education, making it easier to secure funding, justify resources, and improve future program design.

Impact assessment also contributes to the refinement of educational strategies. By identifying strengths and areas for improvement, institutions can adapt their approaches to better align with their educational objectives. This iterative process ensures that cultural heritage educational activities remain relevant, responsive, and meaningful to learners of all ages. Ultimately, impact assessment empowers cultural heritage institutions to maximise their educational impact, strengthen community connections, and contribute to a more informed and culturally enriched society.

Europeana Impact Playbook

The Europeana Impact Assessment Playbook is a resource designed to guide cultural heritage professionals and institutions in evaluating the impact of their digital collections and educational activities. The Playbook offers a structured approach to assessing the impact of cultural heritage activities, including educational programs, exhibitions, and digital collections. It provides step-by-step guidance, tools, and methodologies for planning, conducting, and analysing impact assessments. The playbook covers both qualitative and quantitative methods, enabling institutions to capture a comprehensive view of the outcomes and benefits of their efforts. This digital tool serves as a valuable resource for cultural heritage institutions seeking to better understand the outcomes of their educational initiatives, improve their programming, and demonstrate the societal value of cultural heritage activities to a wide range of stakeholders.

Copyright and educational labels

The public domain encompasses creative works that are not protected by copyright. Such works become part of the public domain through various means, including the expiration of copyright protection, explicit waiver of copyright, or if the work was never subject to copyright protection. Beyond the use that is possible of public domain materials, most copyright laws also establish a range of exceptions and limitations that enable individuals and institutions to utilise copyright-protected works without obtaining permission from the rights holder. Unlike the United States, which has a broad “fair use” provision, the European Union adopts a context-specific approach, with most exceptions and limitations designed to support specific activities within specific contexts.

Among the exceptions and limitations widely recognized in the European Union is the allowance for the display of a work in a classroom setting. This particular exception grants educational institutions the right to use copyrighted materials within the purpose of facilitating effective teaching and learning. The utilisation of digitised AV collections presents school and university educators with exceptional prospects to create valuable learning resources suitable for both classroom and home-based study programs.

Clearing and analysing copyright to understand the reuse possibilities can be a difficult and tedious process. Some cultural heritage institutions, and in particular those sharing data online including via Europeana Platform, try to simplify the information relating to the reuse possibilities of an item through rights statements and/or creative commons licences and tools. These labels make it possible for educators, who often do not have the time to sift through the various copyright labelling, to make a quick and simple assessment on a case by case basis. The following information is organised with this in mind, with the labelling ranging from not suited for use to open access. Europeana, which provides a rich variety of educational resources related to European cultural heritage and serves as a platform for knowledge exchange between museum educators, provides an overview of the labels on their platform.

Copyright Not Evaluated (CNE): This statement is used for works where the copyright status has not been assessed or determined. It is discouraged to use this statement, and it is recommended to evaluate the copyright status before making the works available online.

No Copyright – Other Known Legal Restriction (NoC-OKLR): This statement is applied to public domain works that are subject to legal restrictions other than copyright, which prevent their free re-use.

In Copyright (InC): This statement is used for works that are still protected by copyright. Re-use of these works typically requires additional permission from the rights holder(s). Certain uses might be possible on the basis of exceptions or limitations to copyright.

In Copyright – EU Orphan Work (InC-OW-EU): This statement is used for works that have been identified as orphan works in compliance with the requirements of the national law implementing the Orphan Works Directive in the European Union.

In Copyright – Educational Use Permitted (InC-EDU): This statement is used for in-copyright works for which the rights holder(s) have allowed re-use specifically for educational purposes.

No Copyright – non-commercial re-use only (NoC-NC): This statement is applied to public domain works that have been digitised through a public-private partnership. The contractual agreement limits commercial use for a certain period of time.

Creative Commons – Attribution, Non-Commercial, No Derivatives (CC BY-NC-ND): This Creative Commons licence allows others to download and share the licensed work as long as they attribute the creator, do not make any changes to the work, and use it non-commercially.

Creative Commons – Attribution, Non-Commercial, ShareAlike (CC BY-NC-SA): This Creative Commons licence allows others to remix, tweak, and build upon the licensed work for non-commercial purposes. Any new creations based on the original work must be licensed under the same terms. The creator must be attributed as specified in the licence.

Creative Commons – Attribution, Non-Commercial (CC BY-NC): This Creative Commons licence permits others to remix, tweak, and build upon the licensed work for non-commercial use only. The creator must be attributed as specified in the licence.

Creative Commons – Attribution, No Derivatives (CC BY-ND): This Creative Commons licence allows others to redistribute and make commercial and non-commercial use of the work, as long as no derivative works are shared, and the creator is attributed according to the licence terms.

Creative Commons – Attribution, ShareAlike (CC BY-SA): This Creative Commons licence permits others to remix, tweak, and build upon the licensed work, even for commercial purposes, as long as they attribute the creator and licence their adaptations under the same terms.

Creative Commons – Attribution (CC BY): This Creative Commons licence allows others to distribute, remix, tweak, and build upon the licensed work, even commercially, as long as they attribute the creator as described in the licence.

The Public Domain Mark (PDM): This label is applied to content that is no longer protected by copyright worldwide. Objects marked with this label can be used by anyone without any restrictions.

The Creative Commons CC0 1.0 Universal Public Domain Dedication (CC0): This dedication is used to waive all rights in a work, effectively placing it in the public domain. Anyone can use the object without any restrictions.

Regarding the reuse of Audiovisual material by those within education it is suggested to find materials that meet the criteria of point five or higher as to avoid any potential issues. For those wishing to open up their AV collections to educators there are three labels that might be of particular interest:

1. In Copyright – Educational Use Permitted

This label indicates that the material is protected by copyright and related rights, but it allows for specific educational uses without the need to obtain permission from the rights-holder(s). Educational use is generally considered as non-commercial, instructional use in a formal or informal educational setting, such as classrooms, lectures, research, and study purposes. However, any use beyond educational purposes would require obtaining permission from the rights-holder(s).

This label is beneficial for organisations or institutes with audio-visual materials because it strikes a balance between protecting their content under copyright law and allowing educators to use the material for educational purposes without seeking individual permissions. It encourages the use of their materials in educational settings, increasing their reach and potential impact on learners. This can lead to improved recognition and reputation for the organisation among educators and institutions.

To apply the “In Copyright – Educational Use Permitted” label, the organisation should apply a clear and concise Rights Statement indicating the allowed educational uses. This statement can be made available alongside the audio-visual materials on their website or platform. They should also specify any additional terms, such as attribution requirements or restrictions on non-educational use.

2. Creative Commons – Attribution, Non-Commercial, ShareAlike (BY-NC-SA)

Under this licence, the rightsholder grants others the right to use, remix, modify, and build upon the licensed work for non-commercial purposes. Users are required to attribute the original creator and share their derivative works under the same licence terms (ShareAlike). This licence encourages collaboration, sharing, and creativity while maintaining control over commercial exploitation.

Using this licence for audio-visual materials can attract educators who are looking for resources to enhance their teaching materials. The non-commercial aspect ensures that the content is not exploited for profit, aligning with the non-profit nature of educational institutions. The ShareAlike condition encourages the creation of a larger pool of open educational resources (OER) based on the original material, fostering a collaborative and continuous improvement environment.

For this licence, the organisation needs to add a Creative Commons licence to their audio-visual materials. They can do this by visiting the Creative Commons website (creativecommons.org), choosing the appropriate licence, and generating a licence code. This code can be attached to the materials or mentioned in the Rights Statement to indicate the permissions and requirements for use.

3. The Creative Commons CC0 1.0 Universal Public Domain Dedication (CC0)

CC0 allows creators to waive all their rights and dedicate their work to the public domain, effectively surrendering all copyrights. This means that anyone can use, modify, distribute, or profit from the work without any restrictions or permission requirements. CC0 is particularly useful for creators who want to contribute to the public domain or make their work widely available for reuse.

For organisations that want to maximise the impact and accessibility of their audio-visual materials, choosing CC0 is advantageous. By placing their content in the public domain, they allow educators and learners unrestricted use, modification, and distribution without any legal barriers. This can lead to widespread adoption of their materials in educational settings and beyond, establishing the organisation as a strong supporter of the open knowledge movement. All this whilst also generating traffic to their organisations portals or websites where any services or goods might be being offered for monetary gains.

To dedicate audio-visual materials to the public domain under CC0, the organisation can again visit the Creative Commons website and generate the CC0 Public Domain Dedication. They can then prominently display this dedication alongside or within the materials. It is also a good practice to include a disclaimer that the materials are in the public domain and free from copyright restrictions.

The availability of digitised collections, offering access to digital images and accompanying metadata (such as title, artist, date made, medium, dimensions), greatly amplifies the possibilities of digital heritage for education, learning, research, knowledge sharing, and creativity. It eliminates financial and legal barriers, empowering individuals to explore and utilise these valuable resources to their full potential.

Brief disclaimer regarding copyright

Various copyright labels were briefly described. While things might appear relatively simple on a larger scale, there are usually provisions for educational exceptions at the national level, although it’s not always uncomplicated. Even though there is Europe-wide labelling and copyright, local laws might play a role in determining what AV collections are capable of providing.

Before implementing any changes, licensing, or usage of copyrighted material within an AV collection, it is highly advisable to consult with the appropriate legal department, legal counsel, or a relevant legal authority to ensure compliance with the applicable legislation and regulations applicable to the user’s location. Seeking professional legal advice will help users make well-informed decisions and mitigate potential legal risks associated with copyright violations.

Acquiring a thorough grasp of legal considerations is crucial before delving into any modifications or utilisation of copyrighted content in an AV collection. Thus, seeking advice from legal experts ensures compliance with prevailing laws and confidence in the activities being conducted. On a related note, transitioning to the topic of training, the following training focuses on comprehending rights statements and creative commons licences and tools, fostering an understanding of copyright protection and encouraging informed reuse of digital materials while safeguarding against potential legal pitfalls.

Right Statements (by Europeana Initiative)

The training module ‘Understanding the rights statements used’ provides a comprehensive understanding of the rights statements used by Europeana Initiative to express the reuse possibilities of digital objects and inform how they can be reused. Participants learn about the significance of standardised rights information, gain an overview of various rights statement options, and explore the distinctions between Creative Commons licences, tools, and Rights Statements by the Rights Statements Consortium. This training equips individuals with the knowledge to confidently apply the appropriate rights statements to their digital content, promoting accessibility, discoverability, and lawful reuse of cultural heritage materials.

Selecting Rights Statement (by Europeana Initiative)

The training module ‘How to select an accurate rights statement’ delves into the crucial aspect of accurately selecting rights statements for the data shared with Europeana Initiative. Participants are guided through tips to assess the copyright status of physical objects, navigate legal or contractual considerations, and understand the relation between rights statements and both the content and digital reproductions. By completing this training, participants not only comprehend the importance of precise rights statements but also learn to avoid misleading users and potential legal issues arising from inaccurate rights claims. This knowledge empowers individuals to make informed decisions and foster responsible and lawful reuse of cultural heritage materials.

By participating in both of these trainings, individuals gain a comprehensive understanding of rights statements, their applications, and the implications of their choices. This equips them with the ability to accurately label and manage digital objects, ensuring proper attribution, lawful reuse, and the facilitation of access to cultural heritage materials on Europeana’s platform.

Guidelines for Copyright Management in Cultural Heritage Institutions

In this section, we’ll delve into the strategic steps cultural heritage institutions can undertake to adeptly manage copyright concerns. Drawing from the best practices outlined by Europeana Foundation, we’ll guide you through the process of building a foundation for copyright management, expanding understanding across various roles, and integrating copyright considerations into the daily operations of your institution. For a more in-depth approach and to keep up to date on how to lawfully use your collection in education, consider joining the Europeana Copyright community.

Building Your Organization’s Foundation

During this initial phase, organisations should collectively define their approaches to copyright and (re)use. A coherent approach and policy should be established and adhered to throughout the organisation. Stakeholders, including senior management, licensing specialists, business managers, compliance experts, and digital specialists, play pivotal roles in this process. The top-level policy that emerges should be documented, and external policy documents should be made accessible online. The development of this policy should be closely tied to the strategic objectives of the organisation.

Expansion: Fostering Understanding Across Roles

In the expansion phase, cultural heritage institutions are encouraged to establish a hierarchy of copyright education levels that cater to the various roles within the organisation. Customised guidance and training materials should be crafted for each level, ensuring that every staff member receives the necessary support to comprehend copyright intricacies. By emphasising the risks associated with inadequate copyright knowledge and linking them to the organisation’s strategic goals, institutions can foster a culture of informed compliance.

Integration: Embedding Copyright Considerations

The final phase involves the integration of copyright considerations into the very fabric of the organisation. This includes making the case for essential copyright resources based on project plans, outlining the associated risks and benefits. Integrating copyright into plans, templates, and project proposal documents ensures that copyright is a fundamental aspect of decision-making and project execution.

Glossary & Concepts

AV - Audiovisual

Also written as audio-visual, refers to both the audio and visual aspects of motion pictures or any other media that combines or not sound and images. This encompasses not only films and videos but also various forms of multimedia presentations, recordings, broadcast materials, silent films, audio recordings. Although the term audiovisual connects both video and audio aspects, audiovisual material doesn’t necessarily contain both at the same time. (FIAT/FIAF definition)

Media Literacy